Poem: A further squalid thing

January 16, 2026

The spaces between dog’s toes

are gardens of smell

erupting fungus tickles the nose

with a soupçon of shit.

She stores a safe of comfort there

and sniffs the spaces

to remind her of the day, the week,

perhaps the fragrant year.

Her brain is a sommelier’s,

sensing the slightest hint of dead bird,

the one at the street corner,

and comparing it with the cockatoo

whose carcass she pranced through the park.

The mixture of these avian scents

must be a kind of heaven, a menu

of brown and must, tucked between

those neat non-books of toe.

The title refers to Sei Shōnagon The Pillow Book, the section called Squalid Things. Poem first published Womens Ink!, November 2024

Poem: The Smell of Heaven

October 16, 2025

To a truck driver

Nullabored,

it may be McDonald’s

The dog combines

bone with noseshadow

of absent master

The writer mixes

new printed book wisp

and any wine

Christ died scented

with sweat and piss

and others’ spit

Only a dead-brave poet

would mention roses

but yes, heaven

will be those too,

and we will turn thrice

and smell that which

we smelt in the womb —

warm blood and love.

As that dog, replete

with his master’s tang,

knows meat and bliss

were always one.

PS Cottier

An old poem, this one, first published in Eureka Street ten years ago.

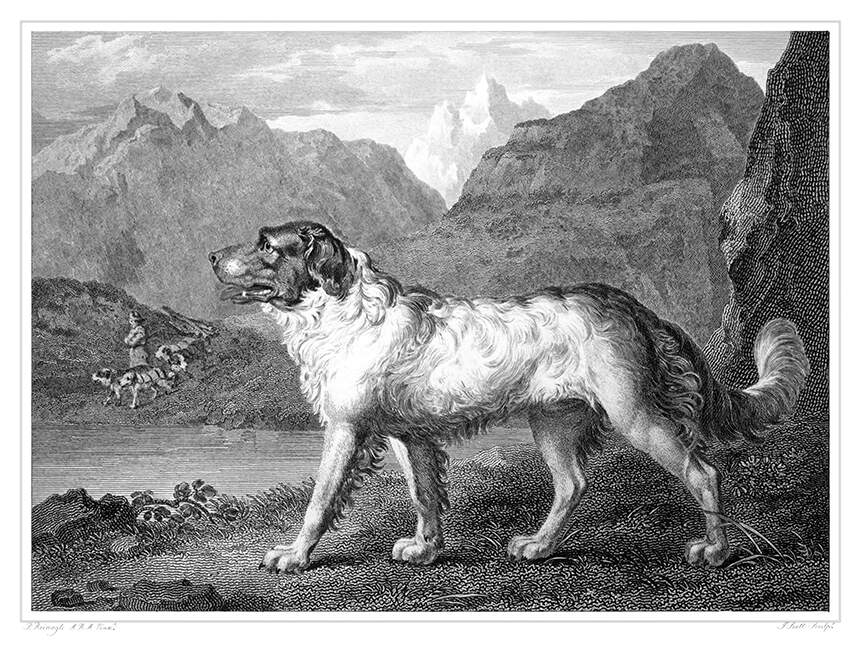

Our sense of smell is so weak, compared to that of the creature in the photo, but I think it’s an important sense to explore in poetry.

Four-legged loss

May 10, 2025

I work the dread so many times

that it’s a kind of sudoku in my head —

rehearsing death like an actor a play.

Hopefully one day she will just not get up,

lie too long in her habitual basket

and avoid that dreaded visit to the vet.

There, liquid death is delivered kindly,

but the syringe is always filled with guilt

alongside yellow pentobarbital.

How can a dog understand that love

might write a prescription for death?

She can’t. She licks my hand, trust

written in the ageing eyes, so cloudy.

Human minds flick through possibility,

feel the knot of loss before death.

But dogs just are. Until they’re not.

PS Cottier

This poem was published in last year’s Grieve anthology, a book made up of entries to a yearly competition organised by the Hunter Writers Centre. The dog who inspired the poem has just died, being put to sleep at home, so I thought I’d republish the poem here. Anyone who has a dog in their life dreads the moment that they die, and believes their dog to be the best in the world. Vale Mango, my much missed Staffie. Fifteen years, and not nearly enough.

Tuesday poem: The paisley pitbull

December 11, 2024

Each bark is Mozart sweet. Silver flutes

are nothing to the improvised flow

of furry sax buried in soft-toffee bay.

His teeth are crochet hooks. Bites bloom

into perennial tattoos, scars in winter

flutter into hollyhocks come spring.

The cat and the kid eat from his bowl,

sip his milk and crunch his kibble,

and the robin plucks hairs for her nest.

He turns three times three before rest,

and apostrophic patterns erupt

as the canine chameleon settles.

Nightbulls may gore; Pamplonas

still run through his veins,

ghost-genes there in blood’s bottle.

But paisley outs. Stretching into dawn,

he shakes off hard history like dew,

and noses, bee-soft, into day.

PS Cottier

This is an old poem, which first appeared in my chapbook Quick bright things: Poems of fantasy and myth (Ginninderra Press, 2016). The dog in the picture was only six back then; now she’s nearer to fifteen.

The poem touches on myths about pitbulls, which can be as affectionate and gentle as any other breed of dog.

Reviews and sniffer dogs

November 18, 2024

The Thirty-One Legs of Vladimir Putin has attracted some thoughtful and positive reviews.

Firstly at Compulsive Reader, where Magdalena Ball wrote the first review of the book. She calls it ‘quirky and strangely haunting’. Secondly, at The Australian. This one is behind a paywall, but the reviewer, Jack Marx, uses phrases like ‘so unusually brilliant’ and states that ‘There is not a bad chapter in The Thirty-One Legs of Vladimir Putin, and a delight of some sort – usually many – on every page.’ It’s enough to make an author blush! Seriously.

In other news, a poem I entered in The Thunderbolt Prize for Crime Writing was commended, which is great. I am working on a short manuscript about dogs, and the poem was about sniffer dogs. You can read the winners here. And here is my poem. And a dog.

Ardent nose

We sniff our way through violence,

the dropped hat or jeans removed,

splatters on grass, the blood-crumbs,

we call them among ourselves.

Some of us disinter computers containing

hidden quests for poisonous feasts.

Here a soupçon of arsenic, there

a sprinkle of fentanyl, adding spice,

designed to remove a troublesome life.

Recipes rarely handed down.

Others detect stashes of drugs,

or cash converted from same,

secreted behind hasty plaster walls.

Our indications cause such a havoc

of mattocks, a stucco snowstorm.

We are taken outside, in case we eat

those attractive disentombed baggies

neatly counted into incriminating piles,

photographed and fussed over.

We’d rather be out after truffles,

chase sticks and toys, roll in dung,

but we sense delight when we unearth

what your dodgy senses cannot catch.

Your poor excuses for olfaction

are unable to detect screams of scent

slapping the face of the air.

My friend, the springer spaniel,

trained from a floppy ball of pup,

all long hair, tongue and wag,

tastes the cadaver air, helps reveal

the buried answer to a search —

for don’t all dogs love bones?

Long before your Poirots or Bosches,

your Holmes after that fog-bound hound,

we sleuths found what you could not find,

found the worst of humankind.

We barked, or sat, and simply waited

for you to finally catch us up.

PS Cottier

Note: The word sleuth derives from slough dog or sleuth-hound, a bloodhound once found in Scotland.